When you teach, you reveal the world's lies. This weekend I've been dispelling the idea the words "universal" or "standard" should ever be written in the world of software - demonstrated through the medium of the arrows in Unified Modelling Language (UML) class diagrams.

UML class diagrams can be used to draw out your object-oriented programming classes and relationships between them. It's essentially a set of paintbrushes you can use to paint the real world into software. Our, quiet, academic arguments centred on how best to represent relationships between classes with different types of UML arrows. Much like other software concepts, its more of an art than a science and multiple answers are always possible.

Arrow Types

One resource I found it tricky to find online was a single, plain English, explanation of the different types of UML arrows - with examples. So let's go through some examples here. Keep in mind throughout my mantra - nothing is universal and you'll see hundreds of different definitions for each of these.

Imagine we have been commissioned to write software for managing a library service and, as grade A software architects (alongside our business analysts), are seeking to model a set of classes.

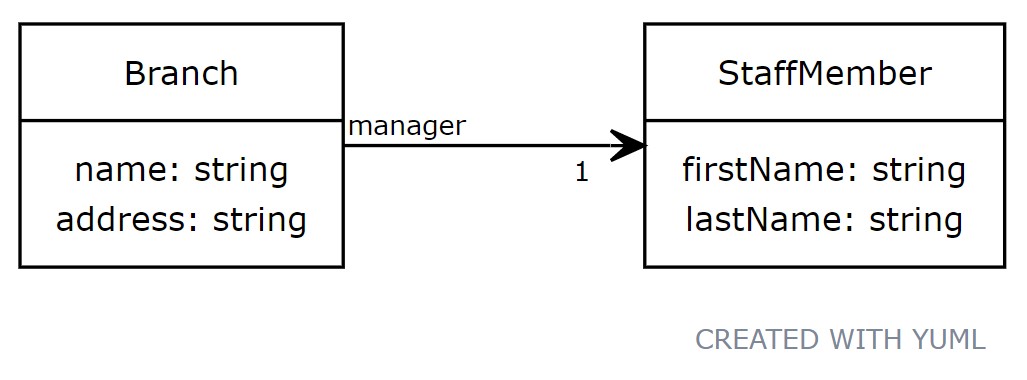

Association (has-a)

The first relationship is perhaps the most general of the lot - showing where one class may act on another. Concretely, this usually means one class has a reference to another and interacts with its methods and/or state. We can also use multiplicity to say how many of each class are involved in an association.

In plain English we might say things like "A branch has one staff member as a manager".

In Java we may write StaffMember manager; in our Branch class.

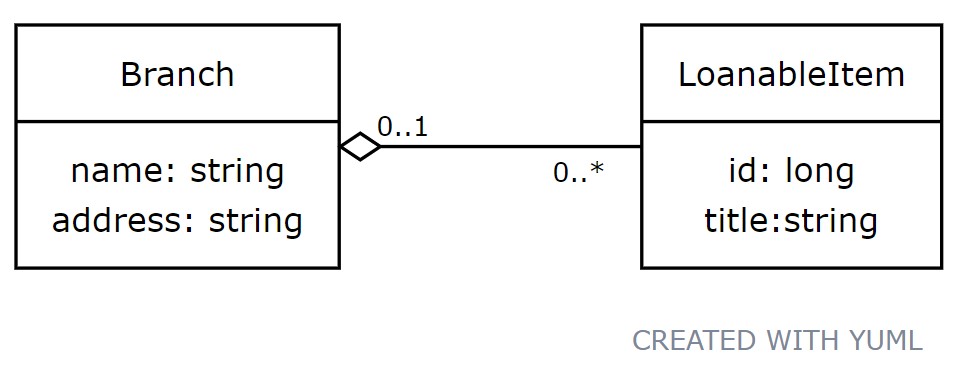

Aggregation (belongs-to)

A more specific type of association is that of aggregation. It represents an association where the object lives on when the object it is aggregated in is destroyed. It is sometimes called a "shared ownership" model.

In plain English we might say things like "A loanable item belongs to a branch. Of course, if a branch closes, the items still belong to our collection.".

In Java we might represent this as List<LoanableItem> stock; in our Branch class whilst also keeping references elsewhere.

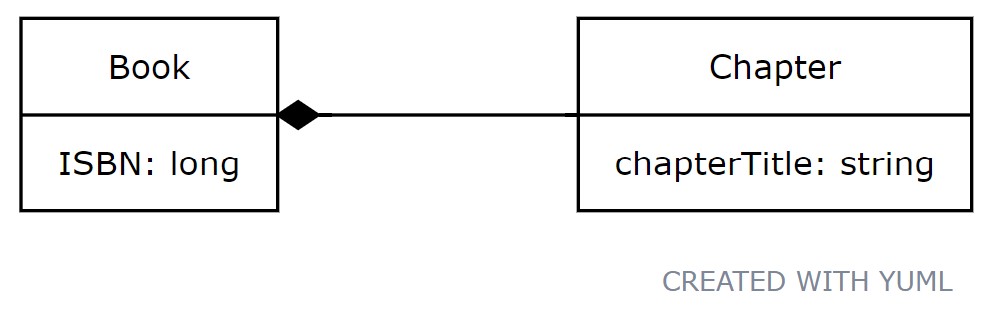

Composition (part-of)

Stronger than aggregation, is composition. This association represents a relationship where the object is destroyed when the object composed of it is destroyed.

In plain English we might say "Chapters are part of a book: without a book the chapters are meaningless.".

In Java we might represent this as List<Chapter> chapters; in our Book class.

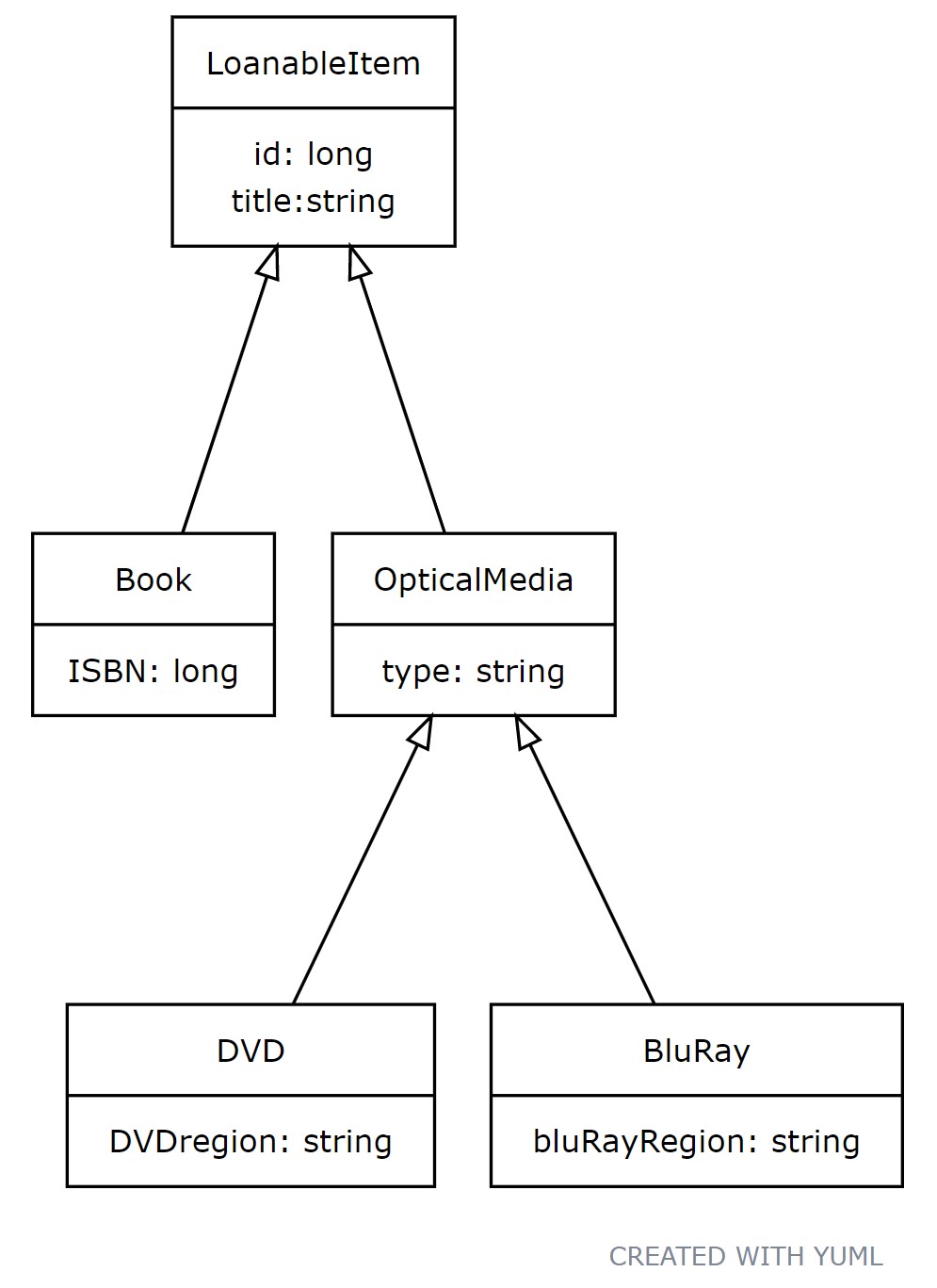

Inheritance (is-a)

This relationship helps us to define a hierarchy between classes in our model going from a more general concept to a more specialised concept.

In plain English we might be saying things like "A book is a loanable item in our library. We two types of optical media: both DVDs and Blu-Rays."

In Java this becomes something like Book extends LoanableItem.

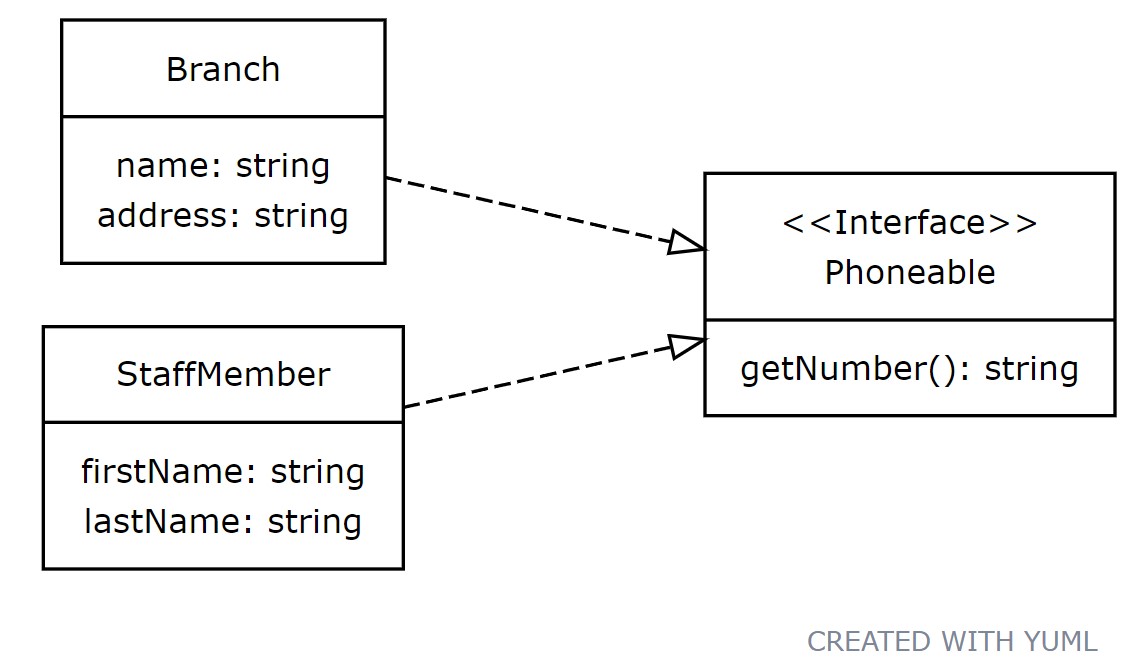

Realisation (implements)

More about behaviour, than structure, the realisation relationship allows us to show what sorts of functionality our class provides.

Our plain English might feature more verbs than other relationships: "We can phone our staff members and our branches when we need to"

In Java this straightforwardly becomes Branch implements Phoneable.

Bibliography

- A. Rice, R. Harle (2021). Object Oriented Programming [PDF Slides]. Available: https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/2122/OOProg/oop-slides.pdf

- Pocketworks Mobile Ltd, "yuml", yuml.me. https://yuml.me/ (accessed Nov. 21, 2022)

- "Explanation of the UML arrows", stackoverflow.com. https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1874049/explanation-of-the-uml-arrows (accessed Nov. 20, 2022)

- Wikipedia, "Class Diagram", en.wikipedia.org. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Class_diagram (accessed Nov. 20, 2022)