So I recently got a new laptop and unlike most Windows PCs of the past forever, it uses an ARM chip and gets pretty amazing performance. So like all the best developers, I set out to squeeze all the performance I could out of it and write an A-list game "Hello World" fully in Assembly.

You might wonder what use there is in learning any Assembly in this day and age, especially if, like me, you are not a driver developer (heck - I'm not even a developer at all).

So, why learn Assembly:

- It's fun

- It's hard

- It gives you an appreciation of the huge amount of work compilers do for us

- It helps you to understand how Operating Systems, like Windows, work

- It gives you an appreciation of the detail that high level languages, and software libraries abstract away

- It makes you really understand primitive data structures and how data is laid out in memory

- It helps you to understand exactly how a specific architecture (in this case AArch64 / arm64 / A64) works

Since Windows on ARM is relatively new, there aren't many tutorials explaining how to write assembly programmes for Windows using A64 assembly. This set of three blog posts fills that gap, getting you to the point where you can write a (totally not for production) "Hello, world!" program using only Windows NT system calls.

Prerequisites

To complete this set of short tutorials, you will need an arm64 Windows laptop (such as a Surface Laptop 7) and a good grasp of core programming and computer science concepts. This set of tutorials is aimed at complete beginners, but if something goes wrong it will be very hard to find your way out without that core knowledge.

Start by installing Microsoft Visual Studio 2022 (NOT Visual Studio Code, you will need VS2022 version 17.4 or later). As part of the install tick "Desktop Development with C++" and ensure the following tools are installed:

- MSVC vXXX - VS 2022 C++ ARM64/ARM64EC

- C++ ATL for latest vXXX build tools (ARM64/ARM64EC)

- Latest copy of Windows SDK

- Just-In-Time debugger

How do processors work - the real basics

A processor is essentially a relatively tiny, incredibly complex, incredibly fast calculator attached to a huge, and relatively much slower, piece of scrap paper (RAM/memory).

It works by fetching, decoding and executing one instruction after another. It will do this one by one unless it encounters an instruction which tells it to jump to another location and start executing a different part of the program.

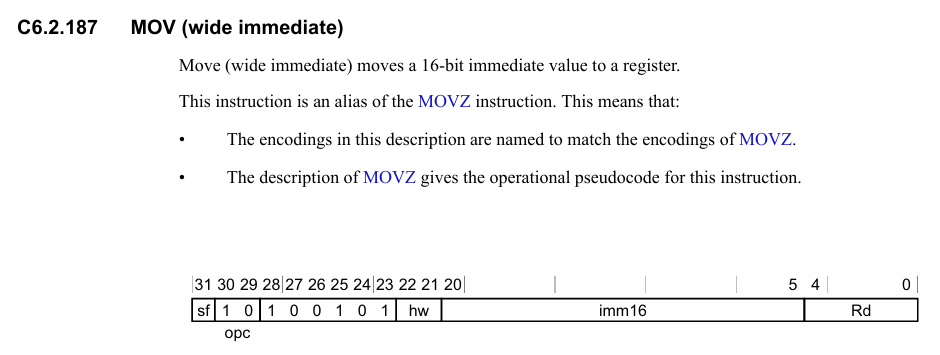

Instructions are represented by small pieces of binary called machine code. Below is an example of an arm64 instruction to set a chosen register to a 16 bit value - each instruction is 32 bits long and these definitions give meaning to the binary.

This image taken from Arm (R) Architecture Reference Manual - Armv8, for Armv8-A architecture profile. It is (C) 2013-2020 Arm Limited or its affiliates

A little about assembly

Assembly is barely even a programming language. It is essentially a way of writing down individual instrutions that a CPU architecture will run without needing to manually write each bit of a machine code instruction down. Depending on the variant, it also includes a few features to help the programmer out such as:

- labels - to help refer to certain things without writing address offsets, and can be exported so the linker can make use of them

- pseudoinstructions - that look like a single instruction but actually compile to several

- directives - which tell the assembler to do something for us at assembly time (such as reserve some memory space in the compiled program, or define, and replace, named constants in our code with values)

To run our code we still need to compile it into machine code that the computer can run, and ensure it's encapsulated in an executable file our OS can start. On Windows this looks like follows:

- Run the code file through the assembler (or compiler) to product a binary object (.obj)

- Use the linker to ensure other required libraries are added to the mix (if needed) and produce an executable (.exe) file

Compiled assembly language works on a single type of architecture and single operating system (or, as we will see in tutorial 3, version of an operating system). Nobody sane writes more than a few bits and pieces in assembly, especially on Windows.

A little about A64 assembly

This does not claim to be the only tutorial out there about A64 assembly - however it is one of the few that contains code written in the dialect of A64 assembly that the Microsoft ARM Assembler supports. If we want to target Windows, we have to use it.

A64 assembly code can be written in either GNU Assembly language (the preferred way) or using "legacy" armasm assembly language, aimed at the standalone compiler. Microsoft's assembler supports the latter, so all code written in this tutorial is aimed at that assembler, and specifically the Microsoft version which doesn't support all the features of the official ARM assembler.

The instructions are the same but the directives and syntax are different so code snippets from other sources may look different and may not work on armasm.

In this language you can stick to all lower case and all upper case for each assembly instruction or directive. To make is clearer in my example code, DIRECTIVES will be all upper case and instructions all lower case.

A little about AArch64 (the arm64 architecture)

One of the oddities of writing assembly code is that you need to really understand how the architecture of the processor you are writing the code for works. Even here we are faced with an abstraction: modern processors are insanely complicated and have a number of features which help code to run faster, but also mean that their behaviour can be unpredictable. Features may also differ between processors of the same architecture but different brands or types for example.

This is unhelpful when writing code, so we define the instructions an abstract version of that processor can run and the rules that code written for that abstract processor must follow. This is called an Instruction Set Architecture, and for arm64, a beginners guide to that can be found here: Learn the architecture - A64 Instruction Set Architecture Guide 1.2.

You can read the whole thing if you like, but the important bits are down below:

- The processor executes one instruction after another (simple sequential execution).

- The processor has 31 general purpose storage spaces (registers) it can make use of, either using the full 64-bits (

x0-x30), or half the width at 32-bits (w0-w30). - There are certain rules for how different pieces of binary code will interact with each other - this is called the Application Binary Interface. It includes things like which registers are used to pass the parameters of functions, and in what way (the procedure call standard - more on this later).

Creating a correctly configured project

This first part of the three will compile a C program and call a function written in arm64 assembly code. By default new projects in Visual Studio do not support assembly so we need to set it up manually.

First create a project that's been properly configured

- Create a new blank solution in Visual Studio

- Create a new blank C++ project called 'Hello'

- Right click the 'Hello' project in Solution Explorer

- Click on 'Build Dependencies' then 'Build Customizations...'

- Select marmasm(.targets, .props)

Writing your first assembly

Create a new file AssemblySource.asm. Into that file insert the following code, written in armasm (A64) syntax. This defines a function that takes two arguments, adds them together and returns the result.

; Test function in A64 assembly language

AREA AsmCode, CODE, READONLY ; marks a code area called AsmCode

EXPORT testfunc ; makes testfunc available to the linker

testfunc FUNCTION

add x0, x0, x1

ret

ENDFUNC

END

Let's dissect this line by line, and then you can read the relevant armasm user guide sections to help you understand more about each command.

AREA

We use the AREA directive to set up independent sections of data and code that the linker can manipulate. In this case we've created a single area called AsmCode, marked it as containing CODE and that it is READONLY. If we tried to modify this section at runtime, we'd get an error.

Labels and EXPORT

In reality, each instruction of our code will have an address in memory (in this case, a 64-bit address). However it would be very very hard to work out what this is ahead of the code being assembled. As a result we can label certain parts of our assembly program so we can refer to them later on.

Here we've created the label testfunc. This essentially tells the assembler to work out what address the instruction add x0, x0, x1 is at and remember it.

If we want to make the label available outside of this code file, we need to mark it for export using the EXPORT directive which tells the assembler to make the label available to the linker.

Procedure Call Standard (AAPCS)

Our ideal processor has no idea what a function is - it only knows registers and instructions. Indeed, functions are an abstract concept used to make programming easier by allowing us to divide up our programs into smaller chunks with defined behaviour - we send parameters into the code, some work gets done, and the result comes out the other end.

As a result, we need a way of defining how functions will work including how to call a function. This part is called the Procedure Call Standard (the link takes you to the arm64 version). Windows follows the Arm defaults for the most part, but a useful summary of all parts and any differences in Windows is documented at: Overview of ARM64 ABI conventions.

We'll learn more as we go, but for now we need to know:

- Function arguments go in

x0-x7before the function is branched to - Function results (if small enough) go in

x0before the function returns

The code we've written is essentially the same (in psuedocode) as function testfunc(a, b) => return a + b;

add & ret

The add x0, x0, x1 instruction performs the following calculation: x0 = x0 + x1.

ret is a bit more complicated. When the function code was branched to (using the bl instruction which the C code below will generate as part of the testfunc(a,b) part), the ARM64 ABI defines that the location to return to is stored in the link register lr. ret is essentially shorthand for branching back to the location stored in lr.

Relevant sections of armasm user guide

Getting it to run from C

Create another new file AssemblyCaller.c. Into that file insert the following C code:

#include <stdio.h>

extern int testfunc(int a, int b);

int main() {

int a = 4;

int b = 5;

printf("Calling assembly function testfunc with x0=%d and x1=%d results in %d\n", a, b, testfunc(a, b));

return(0);

}

Here extern tells the compiler that testfunc is defined somewhere externally and tells the linker that this needs resolving when linking objects. It can then be used in the rest of the C code.

When testfunc is called what is happening?

- Parameter

ais placed intox0and parameterbintox1(as per Arm Architecture Procedure Call Standard (AAPCS)) - The programme counter is changed to point to the memory address of the start of the testfunc section of code (the add instruction)

- The

addinstruction is executed and essentially performsx0=x0+x1wherex0is the location for storing the return value - The next instruction

retis called, which tells the code to go back to the where it was before testfun was called.

Things to try

- Change your code to write a function that takes three arguments and adds them all together before returning the answer

- Try some of the other instructions from the Arm Compiler reference guide.

What next?

In part 2 of 3, we will create some assembly code that runs on its own without any C code to start it off and is able to print "Hello, world!" using the standard C function printf, called from assembly.

Click this link to go to part 2 of 3.